Housing, Not Handcuffs: An interview with housing advocate Maria Foscarinis about Trump’s criminalization of the homeless

Sally O'Driscoll talks to Maria Foscarinis of the National Homelessness Law Center about Trump's forced removal of the homeless in Washington, DC, and the responses of housing advocates.

Photo: Kevin Dietsch | Getty

“Homelessness is not a disease, nor is it an accident; it’s the result of deliberate policy choices made by people. We can make different ones.” – Maria Foscarinis

Housing, Not Handcuffs

Homelessness has rapidly become an even more fraught and nationally visible issue than it was before: when the Trump administration recently took over the policing of Washington, DC, they immediately targeted the “problem” of the homeless as a justification for invoking emergency powers that the president said allow him to send in the National Guard and federal agents. Trump claimed that the city has been “taken over by violent gangs, criminals, and homeless encampments,” and wrote on his social media site that homeless people would have to leave immediately.

“We will give you places to stay, but FAR from the Capital,” he posted. It is not yet clear where these places are, and no new federal funding were appropriated, said DC homeless advocates.

Trump shifted policy from a longtime “Housing First” model that prioritizes permanent housing as a solution to a focus on crime that mandates behavioral health treatment. In response, the National Alliance to End Homelessness, among leading homeless advocacy groups, condemned Trump’s new criteria, warning they might push thousands of people back onto the streets by defunding existing programs.

Homeless advocate and author Maria Foscarinis

Photo: National Homeless Law Center

We turned to Maria Foscarinis for insight into the homelessness crisis and the increasing criminalization of the unhoused. Foscarinis is the founder of the National Homelessness Law Center and the author of And Housing for All: The Fight to End Homelessness in America, just published in June of this year, among many other publications.

Over the past four decades, she has launched and led numerous legislative and policy campaigns to end homelessness and has pursued litigation to enforce and protect the rights of unhoused people. She has been named a Human Rights Hero by the American Bar Association, among many other awards and honors, and is currently an adjunct professor at Columbia Law School. She has unparalleled experience in understanding homelessness and revealing its complex causes – and why it has become an increasing crisis since the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan started cutting social programs. (See her website for more about her book and resources).

In our interview, Foscarinis highlighted past policies that have caused the ongoing surge in the population of unhoused people. The dismantling of federal support for affordable housing began with Reagan, who deeply cut funding for social services, including housing, and then blamed the victims of the cuts by claiming that homeless people reject the available help and are homeless by choice. This cruel rhetoric is still prevalent today, as are regular cuts in funding.

At the beginning of Reagan’s term, the federal government funded over 300,000 housing units per year; the number fell to less than 3,000 per year in 1982. Democrats also joined in, as Bill Clinton did with his policy to “end welfare as we know it.” After more than four decades of cuts, lack of affordable housing has reached crisis levels; the shortage is now so severe that only one in four people who are eligible for housing assistance actually get it.

It’s hard to put a number on the current number of unhoused people in America, since many move in and out of shelters. Under Biden in January 2024, a record-high 771,480 people experienced homelessness in the US on a single night, according to the Housing and Urban Development’s annual Point-in-Time count. That represented an 18 percent increase from 2023, and was primarily linked to the worsening national affordable housing crisis, rising inflation, and stagnating wages. Now add on Trump’s sweeping cuts to federal programs and mass firing of public workers, which have contributed to economic insecurity and joblessness. It’s no surprise that homelessness has risen, along with hunger.

A homeless encampment in Washington, DC. August 2025.

Photo: Jacquelyn Martin

Who are the people experiencing homelessness?

Homelessness occurs in cities, suburbs, and rural areas – anywhere where people live in poverty. About half of the homeless population is employed, but still cannot afford housing. About 20 to 30 percent have mental health or substance abuse issues. Children and families are a significant portion of this population, and are the fastest growing group. About 40 percent are African American, the result of a legacy of segregation and housing discrimination.

While it’s hard to define and quantify homelessness, with many people who fall through the cracks by staying with family or other temporary measures, Reagan’s blame narrative continues to help hide how pervasive homelessness remains.

Why are there so many unhoused people?

The rise in homelessness is linked to a series of Congressional policies. First is a lack of funding for the social safety net that would help people remain self-reliant. People fall into homelessness for many reasons that are beyond their control: for example, loss of work through illness; lack of affordable housing; evictions; and the closing of institutions that used to provide care for the mentally ill. Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill,” reduced public housing and health benefits, including Medicaid, as well as mental health and substance abuse services, while also cutting already inadequate disability services. The federal minimum wage is currently only $7.25 per hour, although some states have higher levels; it has not matched a living wage for decades and reduces the ability to pay rent.

There are many points where interventions could be made to prevent people from falling into homelessness – for example, providing lawyers to represent tenants and stop them from being evicted. Some cities and states require such representation, but don’t adequately fund it, so it is not yet an effective policy.

There is currently a national need for at least seven million housing units for extremely low-income people (including people who have jobs that pay only minimum wage), but the Trump administration’s recent draconian cuts to public housing will only drive that number higher.

HHS federal employees implementing Trump orders to clear an encampment for the unhoused in Washington D.C. near the Kennedy Center.

Photo: Tyrone Turner | WAMU |for NPR

What policies are needed?

The necessary policies that would reduce homelessness are no secret, as Foscarinis explains. She says: “Permanent solutions to homelessness must address its fundamental causes: the shortage of affordable housing, inadequate income to meet basic needs, the lack of social services, and political disenfranchisement.”

It is also important to realize that it is not cost effective to let people fall into homelessness: emergency shelters are expensive, and so is health care provided by emergency rooms. So is jail, and using law enforcement to “sweep” the homeless out of sleeping in public places is also not cheap.

Criminalizing the homeless who live in public spaces

Since the early 1990s, Reagan’s narrative of blaming the homeless themselves rather than the system that creates the crisis has become even more merciless. There is now an ongoing national movement to criminalize the homeless, as evidenced by the surge in local laws that, for example, ban the use of public space for sleeping or asking for money. The administration’s current actions are an attempt to push unhoused people out of sight, to make them invisible and deny that there is a problem. This is a policy that is outlined in Project 2025. For example, it includes a proposal to end “all Housing First directives of Continuum of Care (CoC) grantees and contract homelessness providers in addition to establishing restrictions on local Housing First policies where HUD grant funds are used” (p. 516). Project 2025’s proposed (not yet enacted) cuts to Medicaid will also reduce services to address the mental health issues that contribute to homelessness. The cuts to public housing benefits have already thrown more families into homelessness, without a safety net.

Even where laws to protect the rights of the homeless exist, some try to overturn them: In NYC, there’s a legal requirement that the city provide shelter, and last year it housed 124,000 people. Mayor Eric Adamshas tried to overturn it.

Using law enforcement to “sweep” unhoused people out of sight makes their condition far worse: they may lose their belongings, including ID and critical documents, which are necessary to help keep them out of homelessness. Without an address, it’s also difficult to register to vote or even to receive whatever benefits someone may be eligible for.

There is also a pervasive but false claim that the homeless cause violent crime, which the Trump administration argued as a rationale for using the National Guard to remove homeless encampments in Washington, DC. In fact, the homeless don’t commit crimes so much as violence is used against them. A 2022 report from the Associated Press found that, in Los Angeles, where the unhoused represent just 1 percent of the city’s population, they were the suspects in 11 percent of homicides – but they were the victims in 23 percent of homicides. In fact, there is ample data showing that being homeless exposes people to crime, many times incidents of violence between two unhoused people. An estimated 14 to 21 percent of unhoused people are estimated to have been a victim of violence, compared with around 2 percent of the general population, according to research published in the journal Violence and Victims.

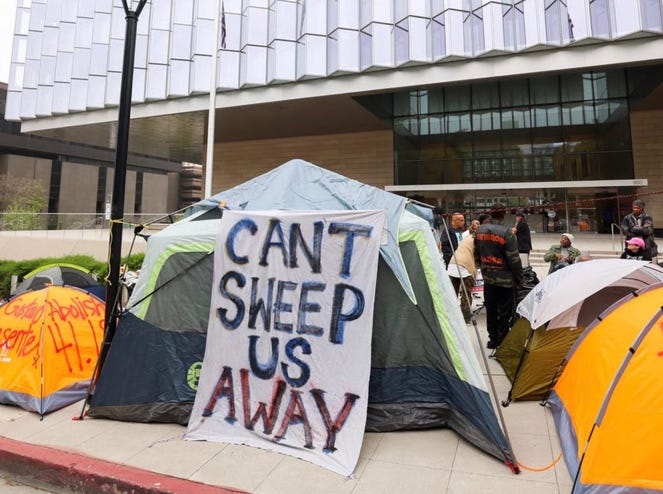

Housing advocates in Los Angeles stage a tent protest at the city courthouse in April 2022 as part of national actions to defend the rights of the unhoused in public spaces.

Photo: Ted Soqui | CalMatters

How to resist: understand that housing is a human right

The concept of housing as a human right is not yet well understood. Unlike Finland’s constitution, the US constitution does not acknowledge the right to housing. This is why Foscarinis wants to reframe the narrative of homelessness – seeing it not as a nuisance but as an issue of human rights. She argues that only when we understand housing as a human right can the crisis be addressed. One way she has done this is through a campaign called Housing Not Handcuffs, which fights against draconian policies and for the concept of human rights.

She urges everyone to sign up on the website for updates on actions, ways to resist, and ways to get involved. The website organizes supporters to protest local and state-level laws that continue to crack down on the homeless. There is actually a bill pending in Congress, the Housing Not Handcuffs Act – it may not have much chance of passing in the current administration, but it’s a focal point of organization.

One successful model of resistance is the House Our Neighbors organization in Seattle, which is effectively advocating for social housing and has passed a city initiative to fund the work. There is also Housing First, which takes a holistic programmatic approach to moving people out of homelessness – Project 2025 calls for eliminating this program and taking away its funding.

The key is this:

In order to address the homelessness crisis, we must recognize it as a man-made disaster. The relentless cutting of the social support network is a policy that deprives people of their rights. The criminalization of the homeless is yet another tactic in this administration’s attempts to divert attention from the real effects of their policies (a transfer of money and power from the larger population into the hands of a billionaire elite) and pushing blame onto a population that cannot defend itself. Resisting that narrative is crucial.

You can listen to my interview with Maria Foscarinis here.

Volunteers offer information and a Metro car to a homeless man outside of the Martin Luther King Jr. Library in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 14, 2025.

Photo: James V. Grimaldi | National Catholic Reporter photo

For more resources:

Don’t forget to check out the Resisting Project 2025 website for additional resources on housing and homelessness, and to learn more about Project 2025’s policy proposals that impact on public housing and programs for those living on the economic margins.

Please consider helping to share this information by restacking this story and sharing the link to our You Tube interview with your social media and contacts. We also welcome feedback from readers.

How many homes would a billion dollars buy? tax the oligarchs now. Billionaires should be eliminated from the financial food chain, they represent a failed system that has been gamed for their profit.