What Works to Stop A Dictator: Global Lessons for America. Argentina. Spotlight on feminist journalist Estefania Pozzo.

“There are only two genders: fascists and anti-fascists.” A spotlight conversation with journalist Estefania Pozzo on countering Milei's war on women's lives and gender and false narratives.

This spotlight conversation is the first of several interviews I conducted recently with Argentine activists, journalists, and political leaders about how they are organizing to confront autocracy and the war on “woke” and gender. It is part of a larger 10-country reporting series on global lessons for America. — ACD

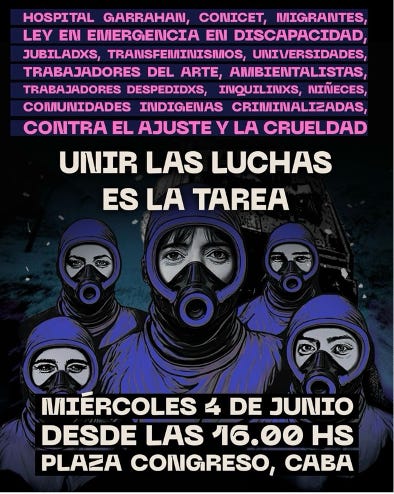

Argentine workers and social justice groups have regularly taken to the streets to protest Milei’s economic libertarian shock doctrine and social policies that reflect his war on “woke” and gender.

Photo: Juan Mabromata | AFP

July 9, Buenos Aires —

“There are only two genders: fascists and anti-fascists.”

On the plane to Buenos Aires in early June, I clicked on a video from the speech Milei had made on January 23 at the World Economic Forum at Davos that outraged a huge slice of Argentines while delighting far-right allies. In it, he outlined his war on “the mental virus of woke ideology” that has “colonized institutions.” He was promoting “an example of a new way of doing politics, which is about telling people the truth to their faces.”

An example of his “truth” was his intensifying war on women’s rights and gender, including LGBTQIA +rights. He denounced feminists and the notion of fighting women’s inequality. He opposed adoption of the word femicide as a label for the killing of women because “this elevated a woman’s worth to more than a man’s.” He didn’t say it there, but his administration is working to remove femicide from the penal code – one item on a growing list of rollbacks of women’s rights. They include his dismantling of the Ministry of Women, Genders, and Diversity, first reduced to a sub-secretariat, then fully eliminated, and his closure of the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Racism (INADI), which oversaw anti-LGBTQIA+ discrimination claims.

In his view, the notion of a gender-based wage gap hid that “there is no inequality for the same work, but rather that most men tend to choose better-paying professions than most women.” He also denounced a “murderous abortion agenda” as a form of population control, “designed on the Malthusian premise that overpopulation will destroy the earth.”

He reserved special animus for his attacks on gender and transgender identity and rights, and what he calls a “culture of sexual relativism.” He minced no words, declaring, “Gender ideology is outright child abuse,” while gender-affirming treatment is a “criminal ideology.” He cited an example of a media report of two gay men — parents — who had filmed their children as a warning against pornography and evidence that same-sex parents should be deemed pedophiles. He didn’t spell out then how he was moving to do that then, but in February, Milei issued an executive decree to prohibit gender-affirming care for individuals under 18, a reversal of part of Argentina’s Gender Identity Law. He also announced that prisoners would be housed according to the gender they were assigned at birth — an anti-trans action — and signaled a plan to repeal legislation that allows for nonbinary identity documents.

In the area of employment, Milei’s government also stopped implementing a trans labor law that called for a small quota of government jobs to be reserved for transgender public employees — a signature policy of the prior Peronist administration. That now leaves many state transgender workers without legal recourse against discrimination or firings.

Milei’s anti-woke austerity shock doctrine has polarized Argentina, drawing major support from the elite and denunciation by a broad sector of the public.

Photo: Fabrice COFFRINI / AFP

Fighting ‘The Party of the State’

In his speech, Milei also laid out his vision of free-trade libertarian economic policies, denouncing socialism and government spending by “the Party of the State” for a range of social ills. He called for a defense of Western culture, including closing borders to immigrants who, he suggested, are responsible for crimes and attacks on citizens. He labeled climate change activists “fanatics.” His anti-woke strategist, Santiago Caputo, reportedly shaped the speech; his sister Karina was in attendance. He told the Davos audience that he had long felt alone in his views, but now, others were embracing them. He felt solidarity with global allies including “the amazing Elon Musk, my dear Georgia Meloni, from Bukele in El Salvador to Vicktor Orbán in Hungary; from Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel to Donald Trump in the United States....”

In other words, a short list of the world’s notable autocrats and aspirants.

Violent protests broke out outside the Congress in Buenos Aires in June 2024 after the Argentine senate approved Milei’s economic reform bill.

Photo: Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty Images

A mobilized opposition

Across Argentina (and Latin America), the Davos speech ignited a fresh flurry of activist organizing by members of the opposition, including longtime feminists and LGBTQIA+ groups. They decided to organize a nationwide Pride protest action on February 1. Across the country, many people got involved in what was seen as a pro-democracy opposition show of force, including many first-time Pride participants. They included members of Argentina’s powerful unions, historically male-dominated, though they include dynamic female leaders. Union activists have been taking to the streets against Milei and his austerity policies since before his election, including some violent clashes that led to arrests. The Pride march notably drew other social sectors, including healthcare workers, students, and retirees who championed a defense of LGBTQIA+ and women’s rights as part of the democracy they defend, as well as immigrant rights.

Before the march, Milei threatened to arrest anyone protesting, and far-right supporters threatened violence on social media. But the march remained peaceful, an outpouring of joy, defiance and celebration, surprising even veteran LGTBQ+ leaders. Rather than intimidate and silence critics, Milei’s Davos speech had united more citizens to join the opposition, including diaspora Argentines and regional allies. Among the many slogans shouted that day was a crowd favorite: There are only two genders: fascists and anti-fascists.”

Photo: Estefania Pozzo

Estefania Pozzo, Journalist, Feminist Activist

My research goal in Argentina was to focus on the status of resistance to Milei’s war on gender and to meet and interview feminists, LGBTQIA+ activists, and political leaders who organized and participated in the recent big Pride march and earlier 2024 feminist and union protests. I wanted to know how these sectors are working together now and learn about regional and global solidarity. I wanted to highlight the role of transgender activists, and hear about how they are coping, giving Milei’s intensified attacks on trans identity and rollbacks of healthcare.

I also had HIV activists on my list, knowing that Trump’s cuts to USAID dramatically impact global funding for HIV programs abroad. Given Milei’s vilification of LGBTQIA+ people, I assumed access to HIV treatments in Argentina may have gotten much more difficult, given its ongoing economic crisis. I also planned to speak to journalists, both foreign and local, who are writing about Milei’s government and looking into its connections to the Trump clan and to ally far-right populists and parties outside Argentina.

Finally, I hoped to dig into a story I’d reported on in 2024 about the links between radical Catholic activists in Opus Dei, right-wing autocratic leaders, and the Project 2025/Trump circle. Opus Dei has had a history in Argentina, and in Spain. I’d read speculation that Milei had gotten support from Spain’s Vox right-wing party, also tied to Opus Dei. What kind of support? I wanted to know.

I had two weeks for my interviews and a packed agenda. Plus, I planned to put on my tourist hat in between work and explore the city’s cultural riches, including museums, and a late-night visit or two to a tango club, including the one where Happy Together was filmed.

The month before my trip, I reached out to journalist colleagues, including a longtime friend and journalist, Henry Scott, who’d invited me to stay with him in the Villa Crespo district of Buenos Aires. It turned out to be a very hip area, full of artsy coffee houses and popular with the growing number of digital nomads, and newer US expats to BA, as the capital is called. Henry can no longer stomach the Trump administration and found a new home there two years ago. He loves the city’s dynamic vibe, diverse culture, the friendliness of porteños, as BA locals are called, its rich art scene, especially street art, and he’s quickly found a welcoming circle of friends in its big LGBTQIA +community, among his reasons for emigrating. Plus he has only good things to say about its healthcare system.

During my stay in BA, I met other NYC expats, some longtime, others newer like Henry, to get their take on life there and how they view the situation at home, by comparison. They were despairing, hungry for news of the US resistance. But they were also glad to have a bit of mental distance on the shitshow, as they label Trump’s latest moves. They are encouraged by the massive street protests and growing resistance, and engaging in acts of solidarity as they can from afar.

Henry immediately pointed me to Estefania Pozzo (Steffi), someone very plugged in to progressive political and activist worlds in Argentina. We spoke by Zoom before I arrived and she provided me with a helpful slew of people and introductions, plus background research. I decided to interview her first, because of her role as both a journalist with a finger on the pulse of Argentina’s political and LGBTQIA+ world and her feminist activism.

Estefania Pozzo with me at the Herald, discussing feminist resistance and media coverage of Milei.

Pozzo wears many hats, being a 40-ish finance journalist and editor-in-chief of the Buenos Aires Herald, as well a feminist and activist. She studied social communication in college, and got two master’s degrees, one in journalism, the other in finance. She also teaches at the University of Buenos Aires, where, she told me, she is very worried about Milei’s attacks on science and research. Like Trump, Milei has moved not only to purge universities of diversity policies, but also to cut funding to eliminate “woke” programs and liberal faculty. (See a recent Herald story on the spending cuts here.)

“Our salaries are so, so low, that a lot of teachers quit the job,” she said, lamenting Milei’s gutting of public education. As an example, she said that Milei not only cut funding for scientists, but his administration combs the database of COCINET, Argentina’s main public research institution for all sciences, including social sciences, for any references to gender, targeting studies for possible cuts or removal. “It’s a word that here, in Spanish, we use in biology in a completely different way, not just gender issues,” she says, explaining that the purge goes beyond research focused on gender. Milei’s administration, she added, is “fighting with science and development itself.”

Her team at the Herald was in the process of putting together a story about what’s happening with Argentine science, and she’s keeping her eye on what is happening in the US, too, seeing many parallels. “I think education is important for individual development, and for social and community purposes,” she stressed. “If you don’t have information, you don’t have education. If you don’t have the right to know what is happening, it’s obviously going to impact negatively on the democracy.”

She’s a member of small feminist publishing collective, Futuros Mejores (Better Futures) that produces research and analysis on feminist topics, including transfeminism. She has closely followed Ni Una Menos, a larger national collective launched in 2015 to focus on violence against women after the brutal femicide of 14-year-old Chiara Páez. She was beaten to death by Manuel Mansilla, her 16-year-old boyfriend, after he learned she was pregnant and refused to have an abortion.

Ni Una Menos was co-founded by a collective of feminist journalists, artists, writers, and activists, and has focused on femicide and a tolerance for domestic violence embedded in Argentine machismso culture. The group’s first national march in Buenos Aires drew 200,000 people. It’s been at the forefront of the fight against Milei’s war on gender, including a strong defense of transgender rights and transfeminism. I was especially interested in speaking to its members, because they helped lead a successful campaign to win abortion rights, which remains legal today, and have been so prominent in the anti-Milei opposition.

Argentine woman marching in the streets Buenos Aires in a January 2024 protest organized by Ni Unos Menos. The sign says: ‘I am looking for my rights, has anyone seen them?’

Photo: Natacha Pisarenko | AP

We met for a formal interview at the modern offices of the Herald, which Pozzo told me is the first English-language newspaper in Latin America, founded in 1876. It seeks to explain Argentina to non-expert readers, and covers politics and human rights, as well as finance – her passion. The paper distinguished itself in the 1970s, covering the longtime military junta that murdered and kidnapped scores of citizens, and the trials and truth and justice process that continues to this day. An estimated 30,000 people who were disappeared have yet to be found, while 400 babies stolen from Argentine mothers detained by the junta and given to other families to raise are also missing. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo formed to search for the disappeared and still-missing and demand justice for the crimes of the junta.

I tend to begin interviews by getting some personal biography, and trying to learn about the values that individuals may have gotten from their families or in response to their social upbringing. Pozzo was born in Cordoba, the second-largest city in Argentina, into a family that was working class and thus sensitive to social issues. Her grandfather was a union leader. “It was really important to pay attention to other people, to fight for justice,” she told me. “These are the family values you grew up with.” Her family was also Catholic, with a small c — meaning that she picked up “a certain level of moral principles from Catholicism... you have a social justice conscience – a community conscience. I think they are, in a way, valuable for living with others.”

She was 11 when she first pretended to be a journalist with a radio show and interviewed her friends about the AMIA terrorist attack — a seminal national event that spurred her political awakening. In 1994, 200 people were killed in a bombing attack at a Jewish community center in the capital. A major memorial was built on the site. She attended Catholic school and, as a teenager, remained preoccupied with the political situation in Argentina. She turned 18 in 2001, the year the country exploded with an economic collapse that led to a major banking crisis and widespread unrest, marked by street protests. A total of five presidents rose and fell in a two-week period as the government struggled to manage the crisis. The GDP fell dramatically; over a quarter of the national workforce lost jobs. Over 30 people were killed in the violence that ensued. “It was a really nasty moment of our history,” Pozzo recalls, shaking her head at the memory. It was also a harsh introduction to adulthood.

Argentine women denounce murders of women in their 2024 Women’s Day march.

Photo: Polo Obrero

The march of women

Pozzo fell into feminism organically, by way of inspiration, when she was in college, studying social communication and media, in 2008. That year marked the launch of a mass gathering of women’s rights activists, the Encuentro Nacional de Mujeres (National Meeting of Women). It was held on the street where she lived; today the event has expanded to embrace transgender women and lesbians. As she explains, “I get out to the balcony and, like, 20,000 women were marching. I was, what is that?! You got very excited.” She laughed, recalling her awakening: “I think I’m a feminist!” From there, she never turned back.

Ni Una Menos began with a strong focus on gender violence, but steadily expanded in 2016 to highlight issues of economic violence and the feminization of poverty, as well as reproductive rights and LGBTQIA+ inclusion. The collective coordinated with similar feminist movements across Latin America, including Mexico, Chile and Peru. In 2018, it played a key role in pushing to legalize abortion, which was signed into law by Peronist Alberto Fernando’s government in December 2020, who succeeded Cristina Kirchner and advanced her social-political agenda.

Kirchner’s support for women’s voices and rights and for protections against gender discrimination (which extended to LGBTQIA+ people, particularly transgender individuals), won her the backing of these sectors, though not immediately. She was always anti-choice until 2018, when she changed her vote to back legal abortion. From 2020 to 2022, Ni Una Mas campaigned to expand gender-sensitive laws, including the Micaela Law that mandated training for public officials, and a survivor-centered gender-based violence (GBV) program called Acompañar.

In 2020, the group also took to the streets during Milei’s presidential campaign to denounce his equation and dismissal of feminism as “cultural Marxism,” and to fight his plan to eliminate the women’s ministry – which he later did. They mobilized against his threats to reverse abortion rights and defund state GBV programs such as Acompañar.

2025 women’s march poster calling for a broad mobilization to counter Milei’s economic policies and their intensification of the feminization of poverty

Photo: Ni Unos Menos

Milei’s war on gender — and especially the poor

In 2024 and again this year, feminists organized nationwide marches to protest his gender policy rollbacks and radical austerity policies, which have had a disproportionate impact on women and the rural poor. In early 2024, government spending on gender-related programs dropped drastically – by 79 percent-- compared to 2023. Milei dissolved the Undersecretariat for Protection Against Gender Violence, which managed the national 144 emergency hotline and, as promised, cut the Acompañar program, ending funding for hotline services and GBV safe houses. (It’s a notable irony, given that Milei suffered a childhood of family violence.)

He eliminated the ENIA Plan, which had reduced teenage pregnancies by 50%; he also cut comprehensive sexual education and reduced funding for maternal and child health programs. Among his anti-trans actions, he also moved to remove nonbinary identities from official documents, while equating LGBTQIA+ rights with child abuse and calling gay men pedophiles.

Over the years, Ni Una Menos focused on the economic impact of social policies on women and girls, an approach that resonates with many in Argentina. A March 8, 2024, “women’s strike” against Milei’s policies focused on the feminization of poverty; at that point, Argentina’s annual inflation rate was 254%. Milei’s cut to Argentina’s 44,000 ollas populares, or community kitchens for the poorest families that are run by social, civil and religious organizations, was a gut-punch to Argentines already struggling to eat. The local kitchens produced about 10 million meals a day in 2023. Ni Una Menos kept the pressure up in 2025, when pensioners and unionized workers from the Garrahan children’s hospital, scientists, and public university teachers joined the annual International Women’s Day march.

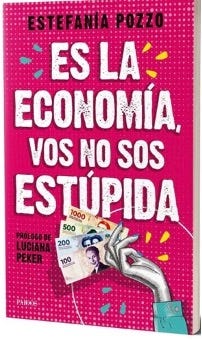

Pozzo’s book on the gender dimensions of Argentina’s economic policy features a prologue by feminist journalist Luciana Peker. She was subjected to threats by right-wing groups even before Milei’s election, and left Argentina for self-exile in Spain after he won, as attacks and threats escalated against feminists and journalists.

A lesson: focus on economic impacts of social issues

As the Herald’s editor and reporter, Pozzo stays focused on the gender dimensions of Milei’s economic platform, among personal priorities. “I think economic autonomy and financial independence are really important for us to defend now,” she says. “There is a link between [them] with the right to choose and to do whatever you want. The autonomy is critical.” That’s a perspective Ni Una Menos advocates. As a professor, Pozzo is also focused on engaging young male students around patriarchy, seeing that as a gap, and a lesson in fighting Milei. As in the US, support for Milei shows a clear gender divide: many women are opposed while a bigger slice of younger men supports Milei.

As a journalist, she also feels it’s critical to document the impact of Milei’s attacks, and to present the data. That’s also where she bemoans Milei’s funding cuts and attacks on science and research, because his administration has ended data collection in some agencies. That makes it harder to know what may be happening in a given sector.

She shared with me a recent forward-looking paper published by Futuros Mejores about trans feminist policy and what is needed to counter the far right’s regressive, pro-traditional family agenda, and efforts to criminalize gender identity. In her view, one task for the opposition and the embattled LGBTQIA+ movement is to reflect on what worked to win the right to legal abortion, and what strategies support a progressive coalition to defend bodily autonomy. “I think it’s important to build bridges between us, and discuss the economic part of patriarchy,” she said, citing the importance of solidarity between lesbians and transgender activists as an example. “I think it’s one of the most difficult parts, because there are a lot of things.”

The National Meetings of Women (Encuentros) have brought thousands of women together annually to debate and organize platforms for action.

I had read that the annual Encuentros had not only brought women together from many sectors of Argentina, but made a tactical pivot at one point that broadened their movement. While feminists had long framed the abortion issue using the rhetoric of women’s rights, they realized that for many women, abortion is a critical economic issue. So is gender-based violence, where women stay trapped in violent homes because they lack economic agency to leave. Anti-abortion activists were often winning the public narrative by advancing moral arguments, using religion and the citing the Bible to denounce abortion as a sin and evil.

So the feminists pivoted. They used the Encuentros to invite thousands of women from all walks of life, not just activists, to talk and testify about how a lack of reproductive choice had limited their futures, and kept them in poverty, or unable to attend school – real life consequences that resonated with a broad sector of Argentines, especially in the midst of Argentina’s protracted economic crisis. They created social messaging giving voice to ordinary women — and their families.

They also engaged men, acknowledging that a lack of means of family planning and unwanted pregnancies impacts heavily on them and their ability to care for their families, too. Importantly, they talked about reproductive rights and GBV programs as human rights, as an aspect of democracy. That tactical shift from a more woman-focused, gendered public narrative toward a broader economic impact one proved critical, as many more women – and men – backed the demand for legal abortion.

The leadership role of progressive Catholics

The other big factor was a leadership role played by Catholics for a Right to Choose. “They did a lot of work, explaining that you can be Catholic and you can support the right to choose,” Pozzo explained. “That’s really important because it’s a way to fight with the men in the church, with the priests who say, ‘abortion is a sin.’ The Catholics for a Right to Choose said, ‘No, it’s not a sin; it’s a matter of human rights. It’s a matter of democracy. It’s a matter of economics.’”

The progressive Catholic activist group designed a signature green scarf widely adopted by feminists who are fighting Milei now. Today, the group works at the federal level and has its people in all the provinces. While Milei seeks to speak as a messenger of God, and for Catholics and evangelical Christians, denouncing feminists and gay people as immoral and evil, the opposition is applying the tactical lesson of reframing its public response to his attacks on gender as anti-democratic, emphasizing democratic principles that resonate with many people, such as individual freedom, as well as the economic impact of his policies. That works.

Union members join pensioners to protest against Milei’s $20 billion loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund in the third general strike against his government, April 9, 2025. |

Photo: Tomas Cuestá | AFP

The role of labor (and men) in broadening the opposition

The issue of the economy is where the labor movement, led by Peronist-affiliated unions, has played a big organizing role, too. Argentina’s unions are very powerful and have led labor protests against Milei’s austerity measures. Their historic presence at the February Pride march in the capital is viewed as a turning point, one in which LGBTQIA+ rights were championed by a broader sector of the populace, marching under a broad banner of democratic rights. They have led major national strikes, including a large on April 9 to protest Milei’s pending $20 billion loan from the IMF — a plan critics said will only impoverish Argentina.

Pozzo joined the massive Pride march where Ni Una Menos was among feminist groups who helped organize rallies across the country, working closely with transgender leaders and labor groups. Many unions turned out, said Pozzo, who said she was surprised by the massive labor turnout and the presence of so many male unionists. “There was even the union of the workers of the construction sector, which is I think 90 percent men — they were there,” she recalled. “This was a first time.” The turnout demonstrated how much Milei’s Davos speech has backfired for him, generating greater support for LGBTQIA+ rights by Argentines and a more unified opposition, transforming a march for Pride into a national pro-democracy statement.

Milei in historic perspective

I wanted to know how Milei compared to prior strongman chapters of Argentine history, in Pozzo’s view, including the military juntas of the 1970s who kidnapped and mass-murdered people. “You can’t compare that with a democracy, because we live in a democracy,” she said, dismissing any comparisons, “but Milei is pushing the limits”. While Milei is acting autocratically, Argentina still has a functioning legal system and an independent media, even if he attacks people and seeks to censor critics and political enemies, she points out.

She cited an example of the Argentine pop star Lali, who was attacked by Milei on social media, called a disparaging nickname and accused of being corrupt, and the case of Ni Unos Menos co-founder and journalist Luciana Peker, who received so many threats that she fled to exile in Spain. Milei also publicly fought with a 12-year-old boy with autism who had spoken out about the impact of federal spending cuts on the disabled. “Milei started to attack him, saying, like, he’s evil and whatever,” recalls Pozzo. “He’s fighting with a boy of 12. I mean, he’s showing himself to be a small man.” The social media attacks are a reflection of the grown-up bully, who, like Trump, attacks those who he perceives as weak Yet the threats are serious. But they are also very dangerous for those on the receiving end. “He is the president, after all,” Pozzo added.

His supporters continue to use social media as a platform to direct their hate and spew disinformation. “And they are really, really violent,” she added. “Things go really badly for some people.” Another factor is the administration’s use of intelligence services that troll social media —- the surveillance of critics is overseen by Santiago Caputo’s team.

On the positive side, Pozzo says Argentina’s courts have provided brakes against some of Milei’s attacks. And media investigations continue to expose corruption and scandals in Milei’s circles. So Milei hasn’t secured two of the key ingredients to consolidate an Orbán-style illiberal state, though he does have a majority of supporters in the Congress.

Right now, inflation continues to be the main political barometer that matters in Argentina. In the 18 months of his tenure, Milei slashed Argentina's record monthly inflation from 25.5% in December 2023 to under 2% as of August 2025. That’s why many support him while holding their nose at his social policies and attacks on women and gay people. But not all is rosy. His radical austerity program has caused recession, and further reduced the purchasing power of Argentines, while his cuts to state services have increased poverty and greatly hurt the working poor.

The result is a split-screen of success that reflects a growing disparity: the wealthiest backing Milei are doing well, and profiting from deregulation policies but the mass of Argentines are suffering from greater daily financial struggles and have lost state benefits. That disparity is what opposition leaders and critics are highlighting to chip away at Milei’s narrative of macroeconomic success and his claim of saving Argentina from failed prior Peronist socialist policies that led to hyper-inflation. By pointing out how Mile’s policies are directly hurting them, the opposition is regaining supporters. The focus on bread-and-butter issues, not so much gender issues, resonates with a larger public.

Is there evidence for hope?

Given the current tide, I asked Pozzo, do you feel hopeful?

“Yes,” she replied thoughtfully, citing her personal sources of hope and faith in Argentina’s future: “Our history… our organizations… the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo… the abuelas... they are a really good example that if you continue fighting, and you’re right and you persist, and you have a strategy, and tactics, and you defend what you believe, at some point you are going to change the reality. So keep fighting. Don’t give up. That gives me hope — to see and learn from our own history.”

Las Madres in 2009

Photo: Beatrice Murch/Flickr

A summary of take-home lessons (as related to countering propaganda, erasure, and the media):

In Argentina, economic survival is a common struggle. Adopting an economic lens to talk about the impact of Milei’s policies on people’s daily lives resonates with voters there and can cut across party lines and political allegiances.

Focus your messaging how people are impacted by policies in their own words, inviting others to connect to their experience.

Milei’s appeal is emotional, playing to people’s fears while pointing to other groups as the reason for their suffering or the threat — a divide-and-conquer strategy. Progressive messages that appeal to emotion also resonate. Personal stories and testimonies by individuals directly impacted by issues are effective, allowing others to emotionally relate.

Milei casts himself as an economic guru, so when a recent financial scandal happened in which people lost money after investing in a crypto currency he touted, it hurt his image and dented public confidence in his policies.

Framing LGBTQIA+ and gender topics as issues of democracy and shared principles of human rights is a useful approach to broaden public support for them. So is linking them to a shared narrative of national identity. That is why Peronism remains popular, too, being linked with positive ideals and a unifying national narrative of social equality and helping others as a shared value that supports national development. Public narratives that elevate how people are connected, and share common dreams, that hold up positive civic ideals, can invite and advance solidarity to counter polarizing rhetoric.

Milei, like Trump and Orbán, is an abuse survivor with a fragile ego who attacks critics and even threatens supporters to control them, while promising to protect them in exchange for loyalty — grown-up bully tactics. His actions can be explained via a focus on his psychological profile. Rather than normalize or downplay Milei’s violent attacks and thin-skinned reactions to criticism, writer Juan Gonzales exposed his history of childhood abuse to reveal a broken man with a history of instability that has helped puncture efforts by Milei’s circle to sanitize Milei’s image as a stable leader. That has helped Argentines better understand Milei’s actions and policies. The focus on Milei’s mysticism (seeking political advice from dead dogs) also call his instincts into question. The point is to avoid normalizing pathological and violent behavior but call it out, and educate the public about it. The focus on personal psychological factors that impact on political leadership can apply to other leaders such as Trump.

It’s no accident that Milei, like Trump, advances a political narrative of male suffering and grievance while promoting male privilege and power, pointing a finger of blame on other groups (women, transgender individuals, immigrants). This is an emotional appeal to tribe and patriarchy that promotes misogyny and reflects a regressive social vision of women’s rights and role. Pozzo feels that it’s important to focus on educating younger men about patriarchy, and feels progressives need to address male emotional pain and needs which Milei (like Trump with MAGA men) has tapped into as a call to tribe. One strategy is to acknowledge the challenges and frustrations facing men but highlight the structural reasons: failing economic policies, etc.

It’s essential to document the direct impact of policies on people’s daily lives by tracking and collecting data about them, and urging the media to cover this, feels Pozzo. Milei, like Trump, has removed science and social science data so people can’t assess the impact on, say, increasing poverty, or environmental safety, or health outcomes. Keeping track of public data, recovering and maintaining data archives is important to provide hard evidence of how people’s lives and national development are affected, and to counter lies, misinformation, and right-wing propaganda.

Engaging allies well-poised to speak on hot-button issues has worked in Argentina: progressive Catholics speaking to other Catholics on topics such as abortion; parents of transgender children talking about their families to counter stereotypes; male unions leaders joining marches to counter attacks on gender. As autocrats target socially vulnerable groups, labeling them threats to others, it’s all the more important to support their voices and leadership in the media and public conversations.

Will you help us share the lessons?

In line with sharing tactics that work, I invite readers to restack this piece and share it on your social media and with your contacts and group who are focused on defending democracy. I invite your feedback and to hear what resonates with you, and what you think about the lessons and insights being shared.

A series special offer:

As many know, I’m offering a major discount on a paid subscription for readers of this global series for a limited time, in an effort to raise needed funds for the field research. My goal is an initial 500 new paid subscribers that will raise half the funds ($12,500) by end December. For just $25, you’ll get a paid subscription to this full series, plus access to a monthly podcast, planned Q&A with me and guests featured in this series so we can talk about the lessons. If the series and lessons resonate with you, I hope you’ll consider that step. If you can afford a full subscription, all the better. I want to thank those of you who are paid subscribers: it’s encouraging me and supports my desire to keep the full content of this series free for those who can’t afford it and we aim to can reach the broadest audience. Grand merci.

Last item: Don’t forget to check out our Resisting Project 2025 website for updates and additional resources on resistance. We welcome tax-exempt donations to that project, and you can also check out our merch swag — another way to support the work and help get the resistance message out.

.

Solidarity is the enemy of the oligarchy. I want to know more about the ‘Green Scarf’ campaign. This is global identity to Solidarity and can be used everywhere.

Can you please share pictures, highlight successful awareness of its meaning and where to purchase in mass? Can you help get global organizers such as independent writers and journalist through independent outlets access to meaning. We cannot wait on global symbolisms to tyranny where we have the means to strengthen Solidarity this very moment.