What Works to Stop a Dictator? In Argentina, decentralization, debate, and learning to listen are first steps in reclaiming democracy .(Pt 1 of 2)

A spotlight on the transfeminist activist group Columna Mostri in Buenos Aires and its goal: “to reconsider how we want to live”. They're also modeling a great way to confront cancel culture.

This article is Part One of a two-part article. See Part Two here. It’s also part of a series of field reports from Argentina and other countries examining the lessons and ingredients of effective resistance to autocracy. See earlier reports here.

Argentina’s “monsters” – a new group of ‘transfeminist’ activists called Columna Mostri, formed to revitalize the queer and feminist movements there and organize an intersectional pro-democracy response to Javier Milei’s autocratic rule.

Photo: courtesy of Columna Mostri

Reclaiming the slur: “We are all monsters.”

One of my key goals in Argentina was to learn more about the groups who organized the huge February pro-democracy march and how they worked together — or not. A number of them were members of a new intersectional activist coalition formed last year called Columna Mostri, led by feminist and LGBTQIA+ activists. The word “mostri” derives from monstruo in Spanish — monster —and reflects a reclaiming of the identity of those who live outside of social margins and are being criminalized by the Milei regime. Many are longtime activists who are also engaged in organizing around labor and climate change, as well as specific issues including the genocide in Gaza. They identify with the leftist Peronist social movement, one aligned with the poor and the labor movement that brings an anti-capitalist critique to Milei’s economic issues.

The Mostris began organically, when a group of seasoned activist friends were chatting on Whats App about their participation in the annual International Women’s Day march, and what actions and responses were needed to counter Milei’s extreme austerity policies and attacks on their communities. This was in January 2024 — hot summertime in Argentina. Milei had been elected in October 2023, promising to reverse gains in women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights, and slash state programs that benefited the working poor, elderly, and homeless, among others. “We were talking about our need for what was missing,” explained veteran feminist organizer and journalist Marta Dillon to me in a June interview in Buenos Aires. “Many of us didn’t feel comfortable marching within the usual feminist columns, where trans and genderqueer men, and cis men, aren’t entirely welcome. Gay men were not allowed to be in the feminist assemblies. So we decided to create a new space.”

Mostris on the march, International Women’s Day, March 2024

Photo: Courtesy of Columna Mostri

The Mostris shared an emotional desire to come together with other activists, something they felt had fallen away during and after Covid in particular. They wanted to re-examine the values that represent a feminist and queer identity for them now. They strongly oppose the anti-trans views of TERFS — trans-exclusionary radical feminists —and also embrace a queer identity that confronts misogyny, and addresses class and labor issues.“We wanted to open up a street space to intervene within feminisms without the restrictions imposed on us in relation to population and identity,” Dillon explained. “We wanted to join March 8 in a way that was intersectional. That is why Columna Mostri was born.”

While Mostris identify as supporters of the leftist Peronist social justice movement, some don’t belong to any political party. That also reflects a historic exclusion of trans-identified people in established political structures, something that is now changing due to queer activism. The call to march under an expanded transfeminist banner also reflects their desire to reach out to those being most targeted and criminalized by Milei’s government, including sex workers, prisoners, the homeless, and undocumented immigrants. But also, seniors, the disabled, and chronically ill people — for whom issues of bodily autonomy, healthcare services, and access to work, insurance, and pensions are important.

“We want to create an alliance of all those who are being put at risk” by Milei’s policies, added Dillon. “Today we are in a situation where Milei is taking a tough action every week. It’s not that we are surprised by what he is doing, though it’s perhaps more accelerated, and much more cruel to some groups like retirees or people with disabilities, where cruelty is paramount. But it’s devastating, because we knew it was going to destroy everything related to feminism, to LGBT rights, to the construction of memory. So we needed to come together to talk about what we must do.”

At the March 8 women’s march, the Mostris were excited when students, the disabled, seniors, progressive educators, and labor activists joined them to march under their transfeminist, intersectional banner.

Marta Dillon, one of the leaders of the Ni Una Menos in its early 90s days, marching for gender justice.

Photo: courtesy of Marta Dillon

Learning from Argentina’s fight against impunity

Dillon is considered an OG feminist by her peers — a member of the old guard who has been a human rights activist for decades. A journalist, she was a founder of Ni Una Menos (Not One [Woman] Less) in 2015, formed to fight femicide and other gender-based violence. “When I was 10 years old, my mother was kidnapped, disappeared, and murdered by the military dictatorship in Argentina. That was in 1976,” she says. That’s when the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo formed, a national movement of mothers of the disappeared, many of them also grandmothers -- las abuelas.

In 1995, an offshoot group called HIJOS (the children) was formed by the children of the disappeared. The Spanish acronym stands for Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice Against Oblivion and Silence. Dillon has been an active member since its inception. Today, HIJOS is a national and transnational organization with thousands of members in Argentina and abroad, reflecting the community of exiled diaspora survivors of Argentina’s so-called ‘Dirty War’. “Our main job was to fight against the impunity of crimes against humanity,” Dillon adds. HIJOS became famous for public actions and protests called escraches (scratches) where members would show up to “mark” the homes or workplaces of ex-military junta members or accomplices accused of perpetrating the disappearances. In the absence of laws against impunity for these junta’s crimes at that time, making them visible was a priority and an “act of memory”, as well as a demand for justice. If there is no justice, there is escrache, goes an HIJOS slogan.

The wheels of justice turned in November 2001, when a three-judge Federal Court of Buenos Aires nullified Argentina’s 1980s amnesty laws, opening the door to the first trials of former junta leaders. This reflected a major victory for the Mothers and HIJOS. Congress annulled the impunity laws in 2003, and the Supreme Court then declared them unconstitutional in 2005. A writer, Dillon turned to investigative journalism and closely covered the justice fight.

In 2010, she learned about the fate of her own mother, Marta Taboada, an activist with the Frente Revolucionario 17 de Octubre who was murdered in February 1977, along with two others, Juan Carlos Arroyo and Gladys Porcel. Their bodies had been buried in a common grave and identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team. Dillon wrote about her mother’s case in the news magazine Pagina ½ and about the judicial process and journey to claim and properly rebury her mother’s body in a memorial ceremony in 2011. In 2015, she published her book about this, Aparecido (Appeared), a blend of autobiography, chronicle, fiction, research, and poetry; it remains the most popular of her eight published books to date. For her, the work of reclamation, memory, and justice continues.

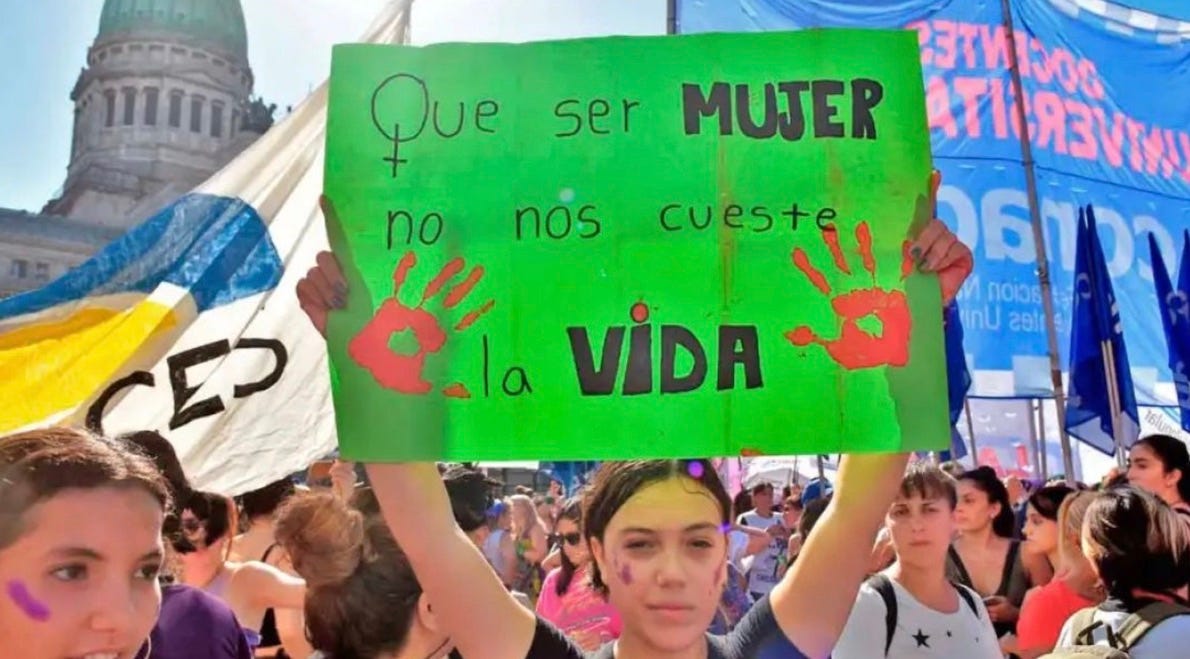

“Life is at Risk! Enough!” Transfeminist Mostris march to protest Milei’s attacks on feminists.

Photo: Columna Mostri

Learning from early feminists

As Dillon explained to me, Argentina’s feminist leaders include political activists who returned from exile and learned about feminism elsewhere. They began organizing large meetings of women in 1986. In 2018, Ni Una Menos organized the first of its annual large-scale encuentros — mass meetings that brought together thousands of women from across social sectors to debate feminist issues including the demand for legal abortion. Ni Una Menos held open-air meetings in small cities and villages, engaging poor and rural women, giving them a platform to talk about the economic and social conditions of their lives, and how poverty and gender roles put them at risk of unwanted pregnancies, and unable to support more children. The issue impacts men and families, and is a basic health right, they argued. That led feminist leaders to pivot and reframe the narrative and public demand for legal abortion as a matter of democracy.

The encuentros serve as a precursor debate model for the now-monthly Columna Mostri asambleas, or assemblies. Ni Una Menos and the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo are among leading groups who helped form Columna Mostri, along with LGBTQIA+, labor, healthcare, climate and education activists. As Dillon explained, she and other Mostris feel the moment is ripe to expand and reclaim the liberation ideals of the early feminist and gay liberation movements, and that includes a strong embrace of transgender rights, but also, a more intentional focus on the economic and social conditions that lead to marginalization. Given Milei’s criminalizing of gender identity, they regard a defense of trans rights and women’s health care as political priorities for pro-democracy activists. (See my recent spotlight with Argentine trans activist Paula Arraigada for more).

The Mothers of the Plaza Mayor have been frontline activists in the anti-Milei battle.

Photo: Columna Mostri

Columna Mostri was launched as a direct response to the ascent of Milei and his far-right libertarian Libertad Avanza party in late 2023, one in which Milei, holding aloft a chainsaw as his signature weapon, declared his war on “woke” leftism and promised to slash federal spending and cut through government bureaucracy and waste while imposing a radical austerity “shock” program to curb Argentina’s inflation. That has increased poverty in Argentina, where many have lost access to prior federal services. The group first formed to march under a unified banner at annual Women’s March on May 11th.

But it’s Milei’s war on gender that has pushed the Mostris to reorganize their trans feminist resistance. Milei, who views himself as a Catholic messenger of God, has moved quickly to reverse key gains of the progressive movement and prior Peronist-led governments related to women’s right, LGBTQIA+ rights, and the rights of the working poor. He is dismissive of being labeled a misogynist and patriarch. He fully eliminated the Ministry of Women, Genders, and Diversity, and is working to remove femicide from the penal code — one item on a growing list of rollbacks of women’s rights. He has denounced a “murderous abortion agenda” as a form of population control and promised to outlaw it. And he has personally attacked feminist leaders and journalists (see more on Milei’s war on feminism in my recent spotlight with Argentine journalist Estefania Pozzo).

As promised, Milei also eliminated the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Racism (INADI), the key institution that has overseen LGBTQIA+ discrimination claims, and also supported the national movement for same-sex marriage. The establishment of the INADI is viewed as a landmark step for LGBTQIA+ movement; its closure is also viewed as a real setback. Milei has focused considerable attention on trans erasure with a series of executive actions, including the prohibition of gender-affirming care for individuals under 18, a reversal of part of Argentina’s Gender Identity Law. He also stopped implementation of a landmark labor law that established a small quota of public jobs for transgender individuals, and ruled that trans prisoners will now be housed according to the gender they were assigned at birth. He plans to repeal legislation that allows for nonbinary identity documents. He also continues to label transgender people and gay men in particular as pedophiles who represent a threat to Argentine youth and families.

“What we’ve been diagnosing is a neofascist government, a government dedicated to social control, and for example, in its state intelligence plan, where it states that we are the target of persecution,” said Dillon. The “we” represent “activists of any kind, but also scientists who study climate change in areas where they might be involved in extraction.” She includes green activists and indigenous groups fighting the petrochemical lobby which is a major ally of Milei.

Like the anti-fascist Spanish brigades that formed to fight Franco, Columna Mostri is made up of people from many different activist collectives. There’s a sex worker collective, “which is about loving,” said Dillon, smiling. There’s a Black-led front that includes several organizations focused on racial justice; a prison right’s collective; a homeless rights and housing collective; and Pride Disca, a disability rights collective. There’s a collective of dissident teachers focused on public education fights, and a number of artist’s and cultural worker’s collectives. Roughly 100 people turned up to the first meeting, but membership has since exploded, growing to 5000 people who attend larger open-area meetings that also involve other political coalitions.

The monthly Mostri asambleas in Buenos Aires often focus on a key discussion theme. When it’s an urgent issue, such as a fresh Milei attack, so many people show up that they need the bigger plazas to debate. Any collective can propose an agenda item for debate. They are more concerned with learning how to listen and disagree first, before they try to agree on a unified agenda or priority platform. Typically, members form small working groups to focus on next steps after the initial discussion.

Decentralization remains key to the Mostris immediate vision of what is needed to reorganize the feminist and queer movements to meet the moment and move forward. Rather than the top-down vertical hierarchies of established political parties, their asambleas are old-school, loose, but moderated discussion forums. Groups who proposed an agenda item present what they are doing, how they view the problem, what is needed, then invite discussion, and problem-solving. Call it the art of debate.

The Mostris regard this approach as an essential building block in order to build trust among activists working in different sectors and collectives who have never worked together, to identify where there are common points of agreement, and where differences of opinion can deepen understanding. But it’s essential that people be heard first — that is the priority. It’s partly a response to cancel culture and social media, Dillon explains, where activists stopped knowing how to listen and respectfully discuss issues without getting stuck or silenced.

Countering isolation

Dillon said the call to unite activists was born of the emergency need to fight Milei and far-right attacks, but also because of divisions that had emerged in the feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements where, she feels, “we had stopped talking to each other and stopped debating issues.” Transgender rights and gender identity, including the battle with TERFS, represented fractures that the far-right camp was exploiting. It’s not only about how to stop Milei, she explained, but refocusing on what progressive activists want and view as priorities now. Topping that list is the ability to hear each other.

“People had stopped meeting in person during Covid,” she said, saying that social isolation became a post-Covid habit, one that also applied to activist groups. While they met to organize marches and actions, “We lost the capability of talking with the people with whom we disagreed. What we are trying to build is the possibility to talk, to make agreements with people. If you can’t hear the other person, or learn to disagree, how can you then agree about what you might want to do?”

In order for people to work together, there needs to be some familiarity and trust, she pointed out. That requires meeting in person, and repeated encounters. Covid helped destroy social bonds; so has social media, where disagreement can quickly go viral and lead to doxing and where cancel culture is a real thing, especially when a regime is invested in weaponizing disinformation and attacking its critics. The fallout of Covid meant people not only shifted to remote work but to an over-reliance on remote organizing. As Milei’s attacks unfurled, the impulse to act felt so urgent, Dillon acknowledged, but what was absent and needed was meeting in person and real dialogue.

Argentina’s annual feminist meetings are a model for the big anti-Milei debates.

Photo: Ni Una Menos

The expanding public conversation

“The thing that needs to be done is to build a discussion, a civic public discussion, and connect people who are very poor in the capital with someone who may have a very strong political identity, so that they two can understand that they have something in common,” Dillon explained, citing an example. That’s also what the Mothers and Ni Una Menos learned in the years of the fight against impunity, bringing people of different experiences together. “That is a reflection of the democracy we want to build,” she added. “This is a moment to build something that is being lost and which gives Milei the opportunity to grow. Part of what we’ve been doing is to generate those spaces of sufficient transversality so that we can actually engage in dialogue,” she says of Columna Mostris’ goals. “That’s the task.”

Columna Mostri defines itself as a transfeminist space, meaning one that is deliberately expanding the discussion and definition of what it means to be a feminist and do queer politics by debating the question of what defines human rights and what are the key values and goals that are, or should be, priorities for these social justice movements now. By transversality, she means taking an intersectional approach to analyzing problems and Milei attacks, and adopting a decentralized approach to organizing, one that understands activists and groups may disagree but have important perspectives to share.

Disagreement is not a problem, per se, but a starting point for analyzing the issue. By sharing their experiences, and how they are responding to Milei, points of agreement and tactics also emerge. Above all, Mostris want to debate and reclaim what they’re fighting for, and to reflect on what a defense of human rights means. “Fundamentally, what’s missing right now is a vision for the future,” she added.” In other words, what we have to reinvent is the question of how we want to live. At least that is what me and my colleagues are trying to address.”

She pauses, asking rhetorically, “Is democracy really what we want? Yes. But, well, we do believe that there must be possibilities for living differently, not at the speed of libertarians and the far right, of extractivism of the planet and then going to live on Mars,” she adds. That last comment refers to Elon Musk’s desire to rehome humans to the red planet in the future. Among issues, the role of AI and technology is also on the Mostri agenda. “Just for today, we want to build ideas. Yes, ideas for ways of life that are less extractive, less competitive, and that allow us other ways of reproducing life that aren’t heteronormative because, well, historically, they’ve killed us in the war of sex... in contempt... in other words, not letting us live.”

End of Part One.

See Part Two for more, including take-home lessons for the US.

Note to Readers:

This global series is a reader-supported endeavor. I invite you to share the contents and lessons it presents by restacking it and sharing links on your social media. I also invite readers to consider an upgrade to a paid subscription to help support the costs of the field reporting. Right now, I’m offering a steep discount of 60% on the cost of an annual subscription for year’s worth of articles — just $25, the cost of a book. A big thank you to those of you who have taken that step to become paid subscribers which is deeply appreciated. I’m also seeking sponsors or possible paid advertisers to help underwrite this work, so I can keep it freely accessible to the largest possible audience. So if you are interested, or know someone who might be, please email me at gendemocracy2025@gmail.com.

You can also find more resources about the US resistance battle on our Resisting Project 2025 website with resources from many frontline groups, and information on the unfolding Project 2025 agenda that is guiding the Trump’s administration’s agenda.